It seems fitting that my first post in eight months should reflect on some of my recent film-related adventures. This long absence was not intentional, but as I dove into my dissertation I had a hard time turning away from it. Since my last report on James Cameron’s use of sound in Avatar, I have been mired in the cagey world of production and post-production sound. The good news is that, after a summer spent indoors, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Ten chapters down, two to go.

Hopefully, I’ll be able to return to blogging on a more regular basis now that the bulk of my tome on modern sound practices has been written. One of the highlights of this past summer occurred when I received an e-mail notification from Paul Brunick at Film Comment / Slant Magazine stating that this site was named one of the top film criticism blogs on the net. It was just the kind of thing to keep me motivated to keep writing. So, despite being late to the party, I would like to thank Mr. Brunick and Matthew Connolly for profiling my site and placing me in such amazing company with other noteworthy blogs like Glenn Kenny’s Some Came Running, Dennis Cozzalio’s Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule, David Bordwell’s Observations on Film Art, Matt Zoller Seitz and the gang at The House Next Door, Jim Emerson’s Scanners, and many others.

While I’m name-dropping film sites, I’d like to also mention the outstanding work of Michael Coleman and his crew at SoundWorks Collection, who have been producing some pretty amazing video profiles on the post-production sound work of major Hollywood releases, including The Social Network. I’d been following Mr. Coleman’s work at Mix Magazine for some time, but last year the SoundWorks project really came into its own as a leading voice in the film sound community.

It’s always nice to see sound editors and mixers talk about the nuances of their work, the challenges they faced, and the creative solutions they devised. Often, filmmakers get short-changed by critics and academics, especially when they talk about their work. We can always learn from what filmmakers say about their work, even if we don’t always believe them or agree with their assessments. In the last few years, the internet has provided a way for filmmakers, especially sound and picture professionals, to speak about the technical and creative aspects of their work. Profiles by SoundWorks and David Poland’s ongoing DP/30 series offer filmmakers a forum to engage with journalists on a variety of issues related to their films in a manner that is more provocative and revealing than your average “Making Of” DVD featurette or Electronic Press Kit.

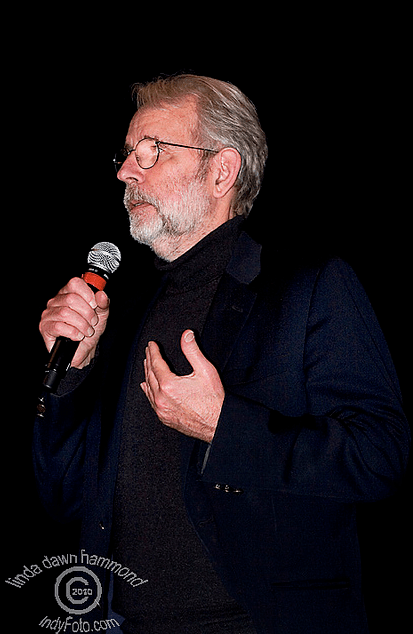

I had an opportunity a few weeks ago to see Apocalypse Now Redux and hear Walter Murch speak about his sound and picture duties on the film. The newly minted Bell Lightbox in downtown Toronto, which is the new home to the Toronto International Film Festival, has been running their 100 Essential Cinema series, which features 35mm, 70mm, and digital presentations of classical and modern favorites, including Apocalypse Now. Murch was in town to participate in a Q & A after the film and to present an original lecture the following night entitled, “The State of Cinema,” which speculated on what would have happened if cinema had been invented in 1789, one hundred years before its actual birth.

It’s seriously about time Toronto had a repertory house for cinema. New York and Los Angeles have a rich tradition of retrospective screenings (with pristine 35mm prints) and special Q&A screenings with filmmakers. The Bell Lightbox project aims to bring the same kind of attention to film classics, and it’s even more impressive that TIFF is inviting filmmakers to speak about their work.

I’ve never met Walter Murch, but his legendary status among sound and picture professionals was in evidence during most of my conversations and interviews with Hollywood sound people. Many contemporary sound editors were eager to discuss particular stylistic aspects to his work, but also reflect on his film-theoretical writing. One conversation in particular about Murch’s “Rule of Two-and-a-Half” inspired me to ask him a question during the Apocalypse Now Q&A.

Over the years, Murch has discussed a series of “rules” and self-imposed limitations in his sound editing and mixing work, but none are more prominent than the “Rule of Two-and-a-Half.” Any sound re-recording mixer must balance a bevy of material in order to compose a comprehensible final track. It’s not uncommon for most sequences to feature dialog, music, and a variety of effects elements that must be married to the picture in a way that does not distort or “step on” the other. Every element has been designed to contribute to the sequence in ways that often go beyond mere redundancy (see it/hear it). In a film as dense as Apocalypse Now, Murch had his work cut out for him.

In the essay “Dense Clarity/Clear Density,” Murch outlines the mixing challenges he faced on the film, and offers a theoretical primer on the nature of film sound and how human brains process sound information. In effect, Murch argues that in order to maintain clarity and density — the two key components of any good mix — one could not include more than two-and-a-half elements from any one group of sounds. Let’s say you have a group of five people walking down a long corridor with linoleum floors. It’s pretty clear that we’re going to need to hear their footsteps, but do we need to hear all five sets of them? Not according to Murch:

Somehow, it seems that our minds can keep track of one person’s footsteps, or even the footsteps of two people, but with three or more people our minds just give up – there are too many steps happening too quickly. As a result, each footstep is no longer evaluated individually, but rather the group of footsteps is evaluated as a single entity, like a musical chord. If the pace of the steps is roughly correct, and it seems as if they are on the right surface, this is apparently enough. In effect, the mind says “Yes, I see a group of people walking down a corridor and what I hear sounds like a group of people walking down a corridor.

To illustrate his point more finely, Murch tells the story of one of Eduoard Manet’s students who was asked to paint a bunch of grapes. “Manet suddenly knocked the brush out of her hand and shouted: ‘Not like that! I don’t give a damn about Every Single Grape! I want you to get the feel of the grapes, how they taste, their color, how the dust shapes them and softens them at the same time.'” With our five characters walking down a hallway, what is important to convey sonically is not the diligent reproduction of each footfall, but the impression of their movements. Three represented the threshold whereupon a group of sounds can be deciphered as parts of a whole and an unintelligible mass.

The Dagwood Sandwich is another Murchian concept. This particular “rule” was applied to a sequence in Apocalypse Now when Kilgore’s men land their helicopters on the beach and begin their combat operations. The sound crew produced six pre-mixes of all the necessary sound elements, presented below in the order of importance:

1. Dialog

2. Helicopters

3. Music (Valkries)

4. Small Arms Fire (AK 47s; M16s)

5. Explosions (Mortars, Grenades, Heavy Artillery)

6. Footsteps and other Foley

Mixing these sound groups together, Murch found that the sound was overbearing. He had created a sound sandwich with too many layers. Everything sounded brown. There was no clarity, just density.

So in this section of Apocalypse, I found I could build a “sandwich” with five layers to it. If I wanted to add something new, I had to take something else away. For instance, when the boy in the helicopter says “I’m not going, I’m not going!” I chose to remove all the music. On a certain logical level, that is not reasonable, because he is actually in the helicopter that is producing the music, so it should be louder there than anywhere else. But for story reasons we needed to hear his dialogue, of course, and I also wanted to emphasize the chaos outside – the AK47’s and mortar fire that he was resisting going into – and the helicopter sound that represented “safety,” as well as the voices of the other members of his unit. So for that brief section, here are the layers:

- Dialogue (“I’m not going! I’m not going!”)

- Other voices, shouts, etc.

- Helicopters

- AK-47’s and M-16s

- Mortar fire.

Under the circumstances, music was the sacrificial victim. The miraculous thing is that you do not hear it go away – you believe that it is still playing even though, as I mentioned earlier, it should be louder here than anywhere else. And, in fact, as soon as this line of dialogue was over, we brought the music back in and sacrificed something else. Every moment in this section is similarly fluid, a kind of shell game where layers are disappearing and reappearing according to the dramatic focus of the moment. It is necessitated by the ‘five-layer’ law, but it is also one of the things that makes the soundtrack exciting to listen to.

In this sense, feel dictated that the music be removed because it affected the general clarity of the scene. Hence, the “Rule of Five” was born.

I asked Murch about his proclivity for sound rules and if they continue to shape his sound mixing work. The short answer was yes, they do. He spoke briefly about his commitment to a dense but clear soundtrack, one that is full of rich details but not overpowering or overly thick. For example, he said that the same sets of conceptual rules governed his mixing work on Cold Mountain.

This sort of rule play guided some of my discussions with other sound supervisors and mixers. Some practice the art of sound mixing using Murch’s principles as a guide or sound Bible. The philosophical aspects to his approach appeals to many top-tier Hollywood sound professionals in much the same way that writers cling to certain well-worn principles of screenwriting. Others, however, expressed a more reserved acceptance of a rule-based account to sound editing and mixing.

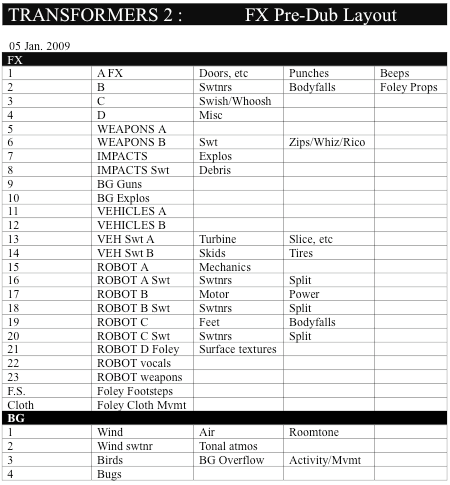

One editor in particular dismissed the need for such strict boundaries. Indeed, one can imagine that the Rule of Two-and-a-Half and the Rule of Five might not apply across the board. In some modern action mixes I am fairly certain that more than five sound groups are operating at one time. In a special editorial for Designing Sound, Transformers sound designer Erik Aadahl explained his pre-mixing strategy for that film’s densely packed sound track. Below is a spreadsheet Aadahl prepared for his pre-dubbed “food groups.”

Notice the sheer amount of FX tracks and BG (background) tracks. There are Foley groups, Background groups, Weapons groups, Hard FX groups, Robot groups, Vehicle groups, Impacts groups, Sweeteners, and miscellaneous groups (“swish/whooshes”). Most of these could theoretically play at one time since they represent actions that can occur simultaneously.

A judicious mixer, according to Murch, must negotiate what food groups constitute “warm” sounds and “cool” sounds, and to try to achieve a balance between them. Too many “cool” sounds — metallics, for example — and you risk oversaturating your “cool” palette; too many “warm” sounds — music, room tones — and you risk the same thing. But it seems likely that in the case of Transformers the Rule of Five was ignored.

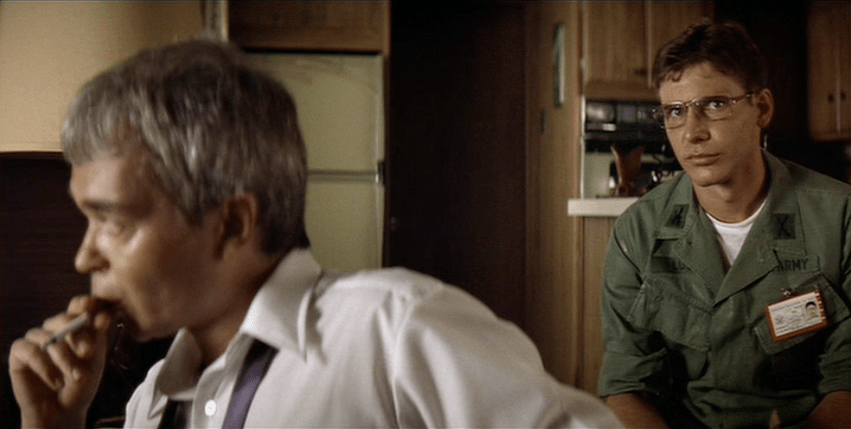

This is not to suggest that Aadahl and the Transformers re-recordists simply saturated the sound track without a plan. A short sequence from the first film illustrates how sound can be absent even though we perceive it to be there. The battle between Optimus Prime and Bonecrusher on the L.A. freeway is a sequence that could very quickly devolve into a muddy, noisy mess. But the final sound mix clean, precise, and surprisingly sparse.

Director Michael Bay breaks up the visual action into clearly defined zones. Using medium-long shots, Bay handles the car-into-bot transformations with a measured approach that respects the spatial geography of the scene and individualizes each action. First, Bonecrusher transforms and proceeds to chase after Optimus, which is followed by a separate shot of Optimus transforming in his own space. The two meet (collide?) in a slowed-down long-lens two-shot. The entire build-up is among Bay’s cleanest from a visual editing perspective.

Sound is equally uncluttered during the build-up. Muting the sequence gives you an idea of how many sound options were available to the filmmakers. Besides the mechanical sounds of the transforming robots, there are stacks of other materials and elements that could be layered into the mix, including pavement being ripped up by the ‘bots, explosions, car impacts, car tire skids, adjacent car engines, background traffic, police sirens, and the vocal “grunts” from the transformers. All of these sound food groups are present at some point during the sequence, but not all at once. Just as Walter Murch eliminated music from the continuous action for a brief moment, the Transformers sound crew emphasized only certain sounds during the continuous traffic chase.

The clip begins with a low-angle tracking shot approaching the Bonecrusher construction vehicle. The camera passes the Decepticon police cruiser with its siren on, and then settles on Bonecrusher as he transforms. The police siren drops out completely and Bonecrusher’s transformation takes center stage, sound-wise. In addition to the servos and hydraulics we also hear the grit of pavement being torn up, followed by some robot vocalizations.

A cut to the rear side of Optimus’ big rig eliminates the other sounds, and we are introduced to Optimus’ “sound world.” Again, traffic backgrounds begin to drop away as he begins his transformation, which is dominated by another set of unique servo and hydraulic noises, pavement and debris elements, and more vocalizations. Keeping a low angle on the action, Bay emphasizes Prime’s claw-foot hitting the ground — cue the impact — which nearly takes out a nearby Cadillac sedan — cue the brake skid.

Each sound element is treated as a unique event, separate from the rest of the FX and background materials. We might even say each sound is its own “shot,” which emphasizes certain key elements. There is very little overlap; in fact, the sequence does not rely on a real-world sense of sound space. At times, the robot vocalizations drown out the FX elements even though there is no reason to suggest they couldn’t share the space with the other sounds. Erik Aadahl and the mixers made a conscious decision to spotlight certain elements and eliminate others completely. It made more sense to them to highlight the vocal personalities of the ‘bots than to continue to emphasize the car/road carnage.

The linear treatment of sound whereby one sound follows another follows closely to Murch’s concept of “clear density” without owing to the rules. Murch found that he could remove a piece of sound from an otherwise busy sequence and the audience would not be consciously aware of it. Similarly, the Transformers freeway chase works on the same principle. As long as hear/see certain spotlighted actions, we don’t need every sound to be continuously employed. We don’t question why, suddenly, Bonecrusher’s destructive transformation drops out when we cut to Optimus Prime.

Some sound editors and mixers refuse to believe they work within a set of rules; in fact, some call themselves sound anarchists, believing that every film presents its own set of challenges and creative options. But it is difficult to imagine that, when faced with a complex action sequence like this one, sound designers and mixers do not adhere to some basic unwritten principles. They may not be the same strategies Murch has used, but they do tend to underscore the same goal: balance. How modern editors and mixers achieve the goal of a balanced sound track depends on who you speak to, but Murch’s career-long pursuit of a perfectly clear and dense track is also one shared by other sound professionals. They might not want to admit it, but even sound anarchists want balance in their work.

Excellent blog. I look further to reading more of your posts.

Glad you’re back! Great post as always. Looking forward to some more, especially concerning your thoughts on Inception and the sound design employed in that film, as well as the music.

This is a ggreat blog